Sudden shortness of breath could be more than just being out of shape

If you’ve ever felt like you can’t catch your breath-even when sitting still-it’s easy to brush it off. Maybe you’re stressed. Maybe you’re just out of shape. But if that breathlessness comes out of nowhere, especially with chest pain or a racing heart, it could be something far more serious: a pulmonary embolism. This isn’t a rare condition. In the U.S., about 100,000 people die from it every year. And too often, it’s missed because the symptoms look like something else.

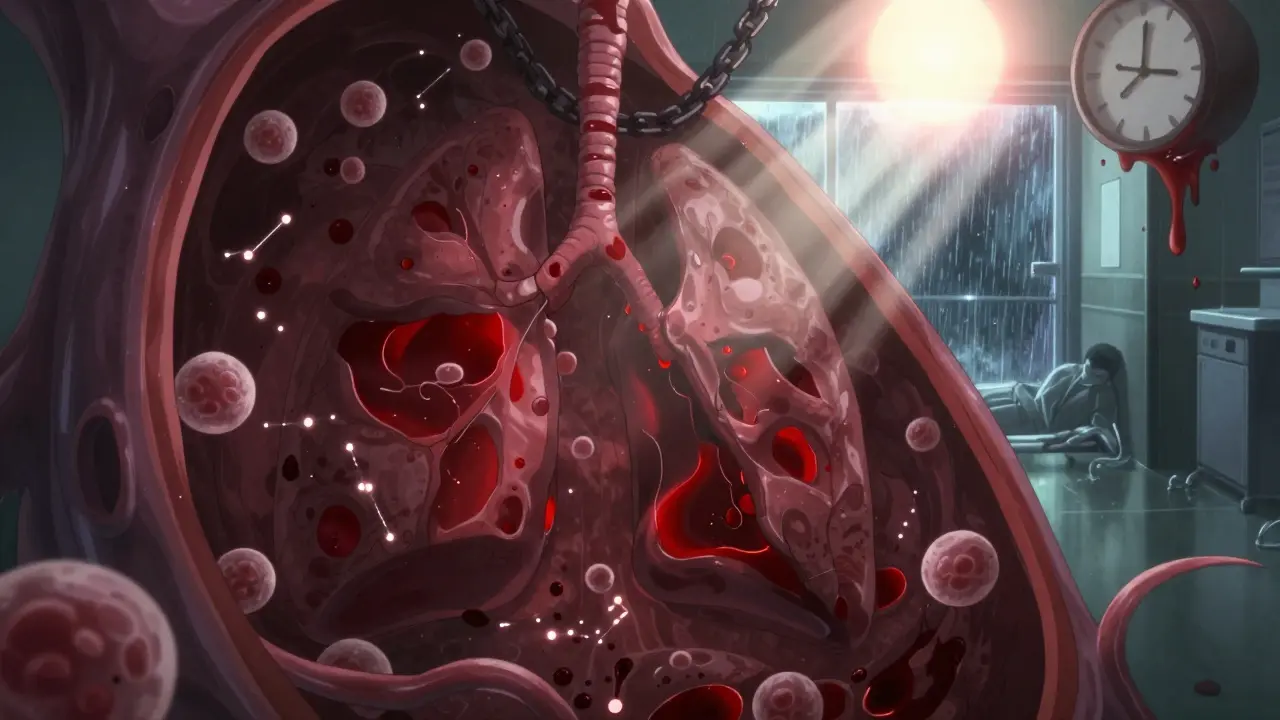

Pulmonary embolism, or PE, happens when a blood clot travels to your lungs and blocks one or more arteries. Most of the time, that clot starts in your leg-a deep vein thrombosis, or DVT. It breaks loose, floats through your bloodstream, and gets stuck where the vessels get narrow: your lungs. Once it’s there, your body can’t get enough oxygen. Your heart has to work harder. And if it’s a large clot, it can shut down your circulation entirely.

What does a pulmonary embolism actually feel like?

There’s no single way it presents. But the most common sign-seen in 85% of cases-is sudden shortness of breath. Not the kind you get after running up stairs. This is different. It’s like someone tied a rope around your chest. You’re trying to breathe, but air won’t come in deep enough. Even sitting still, you feel winded.

For some, the breathlessness comes on so fast they think they’re having a panic attack. Others notice it slowly worsening over days. That’s dangerous. People often delay care, thinking it’s asthma, anxiety, or a bad cold. One patient on a health forum described climbing stairs for three weeks with worsening breathlessness before being diagnosed. Her doctor called it anxiety.

Another key symptom is chest pain-sharp, stabbing, and worse when you breathe in or cough. About 74% of people with PE have this. It’s often mistaken for a heart attack. But unlike heart pain, which tends to feel heavy or crushing, PE chest pain is more like a knife sticking into your side. It’s localized. It flares with each breath.

Other signs to watch for:

- Cough, sometimes with blood (23% of cases)

- Leg swelling or pain, especially in one leg (44%)

- Rapid heartbeat (over 100 beats per minute in 30% of cases)

- Fast breathing (more than 20 breaths per minute in 52%)

- Fainting or dizziness (14%)

If you have any of these-especially together-don’t wait. Call 911. Or go to the ER. Waiting even a few hours can be deadly.

Why is PE so hard to diagnose?

Because the symptoms overlap with so many other things. Asthma. Pneumonia. Anxiety. A pulled muscle. Even the flu. That’s why it takes, on average, 2.3 doctor visits before someone gets the right diagnosis. Nearly half of patients are initially told they have something else.

Doctors have tools to help cut through the noise. The first step is always clinical suspicion. If you’re at risk-recent surgery, long flight, cancer, pregnancy, birth control pills, or a past clot-their radar goes up. They’ll use a scoring system like the Wells Criteria or Geneva Score. These aren’t perfect, but they help. A low score means PE is unlikely. A high score? That’s when things get urgent.

Next comes the D-dimer test. This blood test checks for fragments of broken-down clots. If the result is negative and your risk is low, PE is almost certainly ruled out. It’s 97% accurate at ruling it out. But here’s the catch: if you’re over 50, the test becomes less reliable. The same level that’s normal for a 30-year-old might be elevated in a 70-year-old-even without a clot. That’s why age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds are now standard. For every year over 50, the cutoff goes up by 10 ng/mL. This cuts down on unnecessary scans by over a third.

But if the D-dimer is high-or you’re high risk regardless-the next step is imaging. And that’s where CTPA comes in.

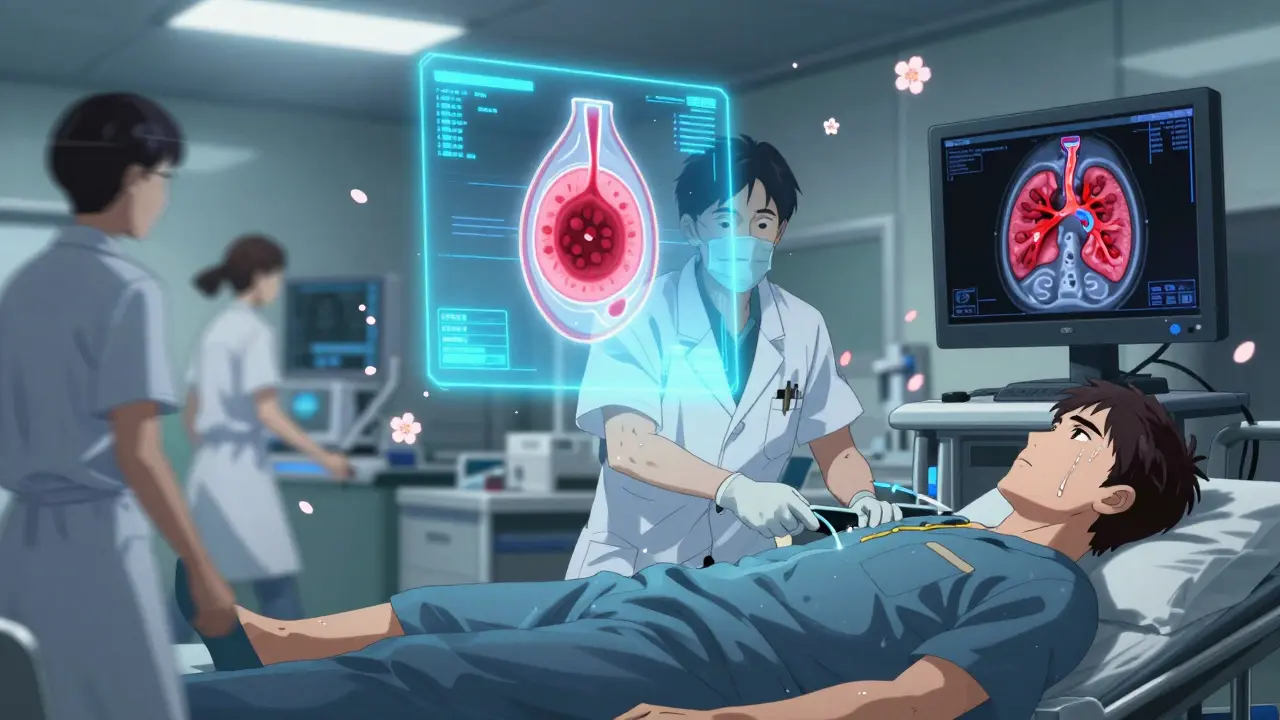

CTPA: The gold standard for finding the clot

Computed Tomography Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA) is the most accurate test for PE. It uses a CT scanner and contrast dye to take detailed pictures of your lung arteries. It finds clots in 95% of cases. And it’s fast. In hospitals with good protocols, the whole process-from walking in to getting results-takes under an hour.

But it’s not perfect. You need IV contrast, which can be risky for people with kidney problems. It also exposes you to radiation-about the same as five chest X-rays. And if you’re allergic to iodine, it’s off the table.

That’s where V/Q scans come in. This test looks at airflow and blood flow in your lungs. It doesn’t need contrast. It’s great for pregnant women or people with kidney issues. It’s 85% sensitive and 95% specific. But it’s not available everywhere. Only 78% of major hospitals in the U.S. have the nuclear medicine equipment needed. In rural areas, that’s a big problem.

And sometimes, doctors skip imaging entirely. If you’re crashing-low blood pressure, fainting, blue lips-they don’t wait for scans. They check your heart with an ultrasound right at the bedside. If your right ventricle is swollen or struggling, that’s a sign of massive PE. Time to treat immediately.

Ultrasound: Finding the source in your leg

One of the smartest moves in PE diagnosis is checking your legs. If you have a clot in your lung, there’s likely one in your leg too. A simple ultrasound of your thigh and calf can find it in over 90% of cases. And if it’s there, that’s confirmation. No need to wait for a CTPA if you’ve already found the source.

It’s quick. It’s painless. It’s done at the bedside. And it’s underused. Many ERs still focus only on the lungs. But finding a DVT changes everything. It confirms the diagnosis. It guides treatment. And it helps prevent future clots.

Who’s at highest risk?

Not everyone gets PE. But some groups are at much higher risk:

- People with cancer-4.7 times more likely to get PE

- Those who’ve had surgery in the last 3 months

- People on long flights or car rides (over 4 hours)

- Women using birth control or hormone therapy

- Those with a family history of blood clots

- People who’ve had a previous PE or DVT-33% will get another within 10 years

And here’s something many don’t realize: if you’ve had a clot before, your body never fully forgets. That’s why doctors keep a close eye on you-even years later.

What’s new in PE diagnosis?

Things are getting faster and smarter. Hospitals are forming Pulmonary Embolism Response Teams (PERT). These are groups of specialists-radiologists, hematologists, ER docs-who jump in when PE is suspected. They make decisions in minutes, not hours. One study showed this cut death rates by 4.1%.

Artificial intelligence is stepping in too. New software can analyze CTPA scans faster than a human. One algorithm, PE-Flow, caught 93.7% of clots with 96.2% accuracy. It’s not replacing doctors-it’s helping them spot tiny clots they might miss.

And researchers are testing new blood markers. Right now, D-dimer is the go-to. But it’s not perfect. New tests looking at proteins like thrombomodulin and plasmin-antiplasmin are showing promise. One trial found a combo test ruled out PE with 98.7% accuracy in intermediate-risk patients. That could mean fewer scans and less radiation.

What happens after diagnosis?

If you’re diagnosed with PE, you’ll start anticoagulants-blood thinners-right away. These don’t dissolve the clot. They stop it from growing. Your body breaks it down over weeks or months. Most people take these for at least three months. Some need them for life, especially if they have cancer or recurring clots.

For massive PE-where your blood pressure drops-you might need clot-busting drugs or even surgery. It’s rare, but life-saving.

Recovery isn’t just about medication. Many people develop long-term breathing problems. That’s called chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. It happens when scar tissue stays in the arteries. If you still feel winded after treatment, ask about follow-up lung tests.

Don’t ignore the signs

Pulmonary embolism doesn’t care if you’re young, fit, or healthy. It strikes without warning. And the biggest danger isn’t the clot-it’s the delay in diagnosis. Too many people are sent home with anxiety or asthma when they’re actually dying.

If you have sudden shortness of breath, especially with chest pain, leg swelling, or dizziness-get help immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t call your primary care doctor and wait for an appointment. Go to the ER. Say, “I think I might have a pulmonary embolism.” That phrase alone can change everything.

The tools to find it are here. The protocols are in place. But they only work if you speak up. Your breath matters. Don’t let it be ignored.

Can a pulmonary embolism go away on its own?

Yes, but it’s dangerous to wait. Your body can slowly dissolve small clots over weeks or months. But larger clots can block blood flow completely, leading to sudden death. Blood thinners are given not because the clot won’t dissolve-but because it could grow or break off again while your body works. Waiting is never recommended.

Is a pulmonary embolism the same as a heart attack?

No. A heart attack happens when a clot blocks an artery feeding your heart muscle. A pulmonary embolism blocks an artery in your lungs. The chest pain can feel similar, but the causes, treatments, and long-term effects are different. A heart attack shows up on an EKG and blood tests for heart enzymes. PE shows up on a CTPA scan. Confusing them can delay life-saving care.

Can you get a pulmonary embolism without having a blood clot in your leg?

It’s rare, but possible. Most clots start in the legs (70% of cases), but they can also form in the arms, especially after IV lines or catheters. Very rarely, clots form in the pelvis, abdomen, or even the heart. If you’ve had recent surgery, trauma, or a central line, your doctor should consider those sources too.

Are blood thinners safe for long-term use?

They’re generally safe, but they carry risks-mainly bleeding. Most people take them for 3 to 6 months. If you have ongoing risk factors-like cancer or a genetic clotting disorder-you might need them longer. Doctors weigh your risk of another clot against your risk of bleeding. Regular check-ups and blood tests help keep you safe.

Can exercise help prevent another pulmonary embolism?

Yes-but only after your doctor says it’s safe. Once you’re on blood thinners and stable, walking regularly improves circulation and lowers your risk of new clots. Avoid long periods of sitting. Get up every hour. Wear compression stockings if recommended. But don’t start intense workouts too soon. Your body needs time to heal.

If I’ve had one pulmonary embolism, will I definitely get another?

No, but your risk is higher. About one in three people who’ve had a PE will have another within 10 years. That’s why doctors look for the cause. Was it a one-time event-like surgery or a long flight? Or is there something deeper, like cancer or a genetic condition? Knowing the cause helps determine how long you need treatment and how closely you need to be monitored.

Can I fly after having a pulmonary embolism?

Usually, yes-but wait at least 2 to 4 weeks after diagnosis and start of treatment. Make sure you’re on blood thinners and feeling stable. During the flight, walk every hour, wear compression socks, and drink water. Avoid alcohol and sleeping pills. If you’re still short of breath or have swelling, talk to your doctor first. Flying too soon increases the risk of another clot.

9 Comments

Michael Bond December 26, 2025 AT 20:26

I had a PE last year. Sudden breathlessness while watching TV. Thought it was anxiety. Turned out I had a clot the size of a grape. Don't wait. Go to the ER.

Matthew Ingersoll December 27, 2025 AT 23:32

The D-dimer age adjustment is critical. My mom was told she was fine at 68 because her D-dimer was 'normal'-but it wasn't adjusted. She ended up in ICU. This post nailed it.

Bryan Woods December 28, 2025 AT 23:45

It is noteworthy that the integration of PERT teams has demonstrably improved clinical outcomes. The multidisciplinary approach ensures that diagnostic delays are minimized and therapeutic interventions are optimized. This represents a significant advancement in emergency vascular care.

wendy parrales fong December 29, 2025 AT 07:56

I used to think shortness of breath was just me being out of shape. Then my sister almost died. Now I tell everyone: if it feels wrong, it probably is. Don't let anyone gaslight you out of getting checked.

Jeanette Jeffrey December 29, 2025 AT 17:26

Wow. Another 'you might die if you don't go to the ER' post. Newsflash: everyone with a pulse has anxiety. You think every wheeze is a clot? Go breathe into a paper bag and stop panic-shopping medical advice.

Shreyash Gupta December 30, 2025 AT 23:54

I think this is all fearmongering 🤔. I'm from India and people here don't even know what CTPA is. My uncle had chest pain for months, went to 3 doctors, they all said 'stress'. He's fine now. Maybe we don't need all this tech?

Dan Alatepe January 1, 2026 AT 06:11

Man... I thought I was just tired. Then my leg swelled up like a balloon and I couldn't walk. Took me 2 weeks to get someone to listen. Now I'm on blood thinners for life. This post? It saved my life. Thank you.

Angela Spagnolo January 2, 2026 AT 06:39

I... I didn't know about the age-adjusted D-dimer... I'm so glad I read this. My dad was sent home last year with 'anxiety'... I didn't know to ask... I'm so scared... I hope he's okay...

Sarah Holmes January 2, 2026 AT 08:27

This post is dangerously irresponsible. You're inciting mass hysteria over normal physiological variations. Most people who experience occasional dyspnea do not have PE. You're eroding trust in primary care by implying that every breathless person is minutes from death. This is medical malpractice in narrative form.